Britannophiles, unite!

Money wasn’t scarce growing up, but it also didn’t grow on trees. Movie theatres were a rarity: we waited until the release on VHS. The only “official” movies we had were gifts. Rarely, very rarely, we would rent a film from the local video rental shop – before it turned into a Blockbuster – but more often, we would borrow films from our favourite library. In order to be sure that we would always have some entertainment on hand, my mother would peruse diligently the TV guide as soon as it was delivered to the front door, and plan out what she would record for the week. She built up a huge collection of almost 100 tapes that way. She had the index cards and descriptions to go with it! We spent many a Friday or Saturday night in front of the TV, next to the fireplace, with homemade popcorn, watching one of the movies my mother had taped for us. Often it was a British piece, sometimes period (Pride and Prejudice anyone? The 1995 BBC mini-series with Colin Firth, obviously), sometimes comedy (Fawlty Towers, Keeping Up Appearances, Absolutely Fabulous) and often detective novels (Miss Marple, Hercule Poirot, Bertie & Wooster).

My mother adored detective novels. She tried to share that same passion with me via these movie nights, but I never did get to the same levels of enthusiasm as she: I found the plots clever, but forgettable. So forget them I did. It is only now that I am much older that I find myself gravitating back to the genre: there is something comforting about a world where everyone agrees that bad people deserve to be tracked down and held accountable and where the truth always comes to light. Whenever I am feeling overwhelmed by life, and need a little reassurance, I dip into my mother’s collection and settle down for a cozy read, curled up on the couch, tucked under some warm blankets. I emerge a few hours later with a sense of satisfaction and peace with the world.

Whose Body?

Whose Body? was first published in 1923 by Dorothy L. Sayers. It was her first novel, and she was not yet 30 years old; she wrote it to distract herself of a broken heart. It was an immediate best-seller, and immediately cemented her as one of the top crime novelists of her era. And what an era it was! The 1920s and 1930s are now known as the Golden Age of Detective Novels, producing famous novelists such as Agatha Christie (Miss Marple, Hercule Poirot), G.K. Chesterton (Father Brown), Josephine Tey (The Daughter of Time), Georgette Heyer, are just some of the enduring British ones, whose works are continuously republished or picked up for movie production to this day.

Whose Body? introduces us to Lord Peter Wimsey, a wealthy aristocrat recovering from what we would now call PTSD from his time serving in WWII, and Detective Parker, a young man from modest circumstances who chose a life of service in the police force over his twin calling of theology. These two form an unlikely duo, with Lord Peter fulfilling the role of civilian sleuth, similar to Sherlock Holmes, less the unlikely mental prowess and memory. Lord Peter is smart, no doubt, but no smarter than those reading his stories. This makes him more accessible, and the stories more relatable, that those of Lord Peter’s more well-known predecessor.

The plot of the book centers around 2 unrelated events: the naked body of an unknown man is found in an architect’s bathtub with a golden pince-nez, and a famous financier disappears days before concluding a controversial transaction.

Mr. Parker made the encouraging noise which, among laymen, supplies the place of the priest’s insinuating, ‘Yes, my son?’

One thing that struck me was the subtle humor sprinkled throughout the story; it does not distract from the story at hand, as it is gently woven into the descriptions, here and there.

‘Oh that’s nothing,’ said Mr. Milligan, ‘we haven’t any fine old crusted buildings like yours over on our side, so it’s a privilege to be allowed to drop a little kerosene into the worm-holes when we hear of one in the old country suffering from senile decay.’

Mr. Milligan is an extremely wealthy American, speaking to Lord Peter’s mother, the Dowager Duchess of Denver, who is leading fundraising efforts for the roof of the church Parish. Dorothy L. Sayers is particularly skilled at capturing clashing social norms that existed at the time with humor, and never at the expense of one demographic over the other.

“Very curious, dear. But so sad about poor Sir Reuben. I must write a few lines to Lady Levy; I used to know her quite well, you know, dear, down in Hampshire, when she was a girl. Christine Ford, she was then, and I remember so well the dreadful trouble there was about her marrying a Jew. That was before he made his money, of course, in that oil business out in America. The family wanted her to marry Julian Freke, who did so well afterwards and was connected with the family, but she fell in love with this Mr. Levy and eloped with him. He was very handsome, then, you know, dear, in a foreign-looking way, but he hadn’t any means, and the Fords didn’t like his religion. Of course we’re all Jews nowadays, and they wouldn’t have minded so much if he’d pretended to be something else, like that Mr. Simons we met at Mrs. Porchester’s, who always tells everybody that he got his nose in Italy at the Renaissance, and claims to be descended somehow or other from La Bella Simonetta – so foolish, you know, dear – as if anybody believed it; and I’m sure some Jews are very good people, and personally I’d much rather they believed something, though of course it must make it very inconvenient, what with not working on Saturdays and circumcising the poor little babies and everything depending on the new moon and that funny kind of meat they have with such a slang-sounding name, and never being able to have bacon for breakfast. Still, there it was, and it was much better for he girl to marry him if she was really fond of him.”

The Dowager Duchess of Denver, to her son Lord Peter Wimsey

I was shocked when I read this passage; I still am. I remind myself that this book was written a century ago, and that I should be grateful for the opportunity to see so sharply the biases that existed not-so-long ago. Given the advent of WWII a mere 16 years later, I’d posit these views are generous for the time: they seem to be anchored in ignorance, without any bigotry or hatred. What rattles me the most is that we cannot say in good faith that much progress has been made since then. If not these views then other populations are spoken of just as casually, with damning consequences (Palestinians, for example).

‘That’s what I’m ashamed of, really,’ said Lord Peter. ‘It is a game to me, to begin with, and I go on cheerfully, and then I suddenly see that somebody is going to be hurt, and I want to get out of it.”

‘Yes, yes, I know,’ said the detective, ‘but that’s because you’re thinking about your attitude. You want to be consistent, you want to look pretty, you want to swagger debonairly through a comedy of puppets or else to stalk magnificently through a tragedy of human sorrows and things. But that’s childish. If you’ve any duty to society in the way of finding out the truth about murders, you must do it in any attitude that comes handy. You want to be elegant and detached? That’s all right, if you find the truth out that way, but it hasn’t any value in itself, you know. You want to look dignified and consistent – what’s that got to do with it? You want to hunt down a murderer for the sport of the thing and then shake hands with him and say, “Well played – hard luck – you shall have your revenge tomorrow!” Well, you can’t do it like that. Life’s not a football match. You want to be a sportsman. You can’t be a sportsman. You’re a responsible person.”

‘I don’t think you ought to read so much theology,’ said Lord Peter. ‘It has a brutalizing influence.’

As someone who has spent much of her time on this planet approaching life as a game, I wish I’d had me a Detective Parker to call me out on my bullshit a bit sooner. Who knew detective novels carried such valuable insights?

An unexpected resemblance with a sprinkling of grief

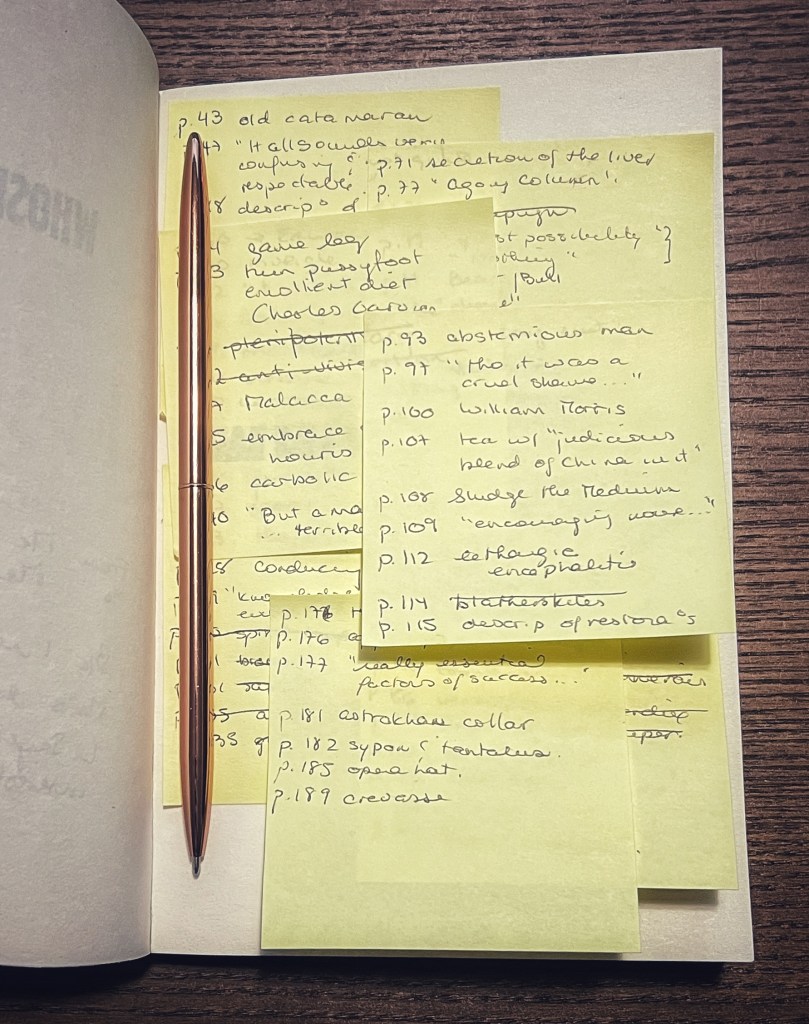

As I sort through my mother’s books, I am finding countless mementos. Sometimes she’d keep newspaper clippings about the author or the book. Often, the back pages of the book are scribbled with notes and post-its highlighting her favorite passages, or questions to reflect on. What a mama.

With this blogging journey, I’ve noticed I read with greater intentionality: I keep post-its nearby, and I track the words I am not familiar along with the passages that strike me as memorable. For example, for this 191 page book, I gathered 7 post-its full of scribbles – just like my mother. I very much enjoyed this book, just like my mother. I didn’t find the plot forgettable, at all.

When I began sorting through my mother’s books, it was clear that there were too many for me to take with me: I live in a floor of a townhouse, 1000 sqft, there was just not enough continuous wallspace for me to build the necessary custom bookshelves to accommodate her entire collection. My mother had an entire double-bookshelf double stacked with detective novels. I rolled my eyes, and packed them all up into boxes – the first to be given away to charity. I didn’t recognize any of the authors names then; I now realize she had close to the complete works of most of the great detective novelists from the Golden Age of Detective Novels! I chose to discard them without a glance. And now, several years later, that I’ve realized that I do share my mother’s enjoyment of this genre, it’s all gone, one of the few tangible links I with her, broken by my own impatience.

It hurts.

A few words I discovered while reading this book:

- Apperception: (n.) the mental process by which a person makes sense of an idea by assimilating it to the body of ideas he or she already possesses.

- Blatherskite: (n.) a person who talks at great length without making much sense.

- Bromide: (n.) chemical compound used in the early 1900s as a sedative.

- Edmond de la Pommerais: (1836-1864) a French physician, murdered his mother-in-law and his former mistress in the 1860s. He persuaded the latter to fake an illness in order to collect an insurance settlement, and to write a letter describing her phony problems; after which he poisoned her with digitalis.

- Gambol: (v.) to run or jump around playfully.

- Henry Wainwright: (1832-1875) an English shop-owner, who murdered his mistress to avoid the discovery of the affair by his wife, and buried the body under the floor boards of a warehouse he owned. A year late, strapped for cash, wanting to sell the warehouse but worried the stench of the decomposing body might affect the selling price, he dug up the remains, dismembered them, and attempted to have moved by cab to a different location. The smell of the parcels led to his discovery.

- Impugn: (v.) dispute the truth, validity, or honesty of (a statement or motive); call into question.

- Munificent: (adj.) (of a gift or a sum of money) larger or more generous than is usual or necessary.

- Pea-Souper: (n.) a very thick fog.

- Peritonitis: (n.) a redness and swelling (inflammation) of the lining of the belly or abdomen. This lining is called the peritoneum. It is often caused by an infection from a hole in the bowel or a burst appendix.

- Perspicuity: (n.) the ability to think, speak or write clearly.

- Plenipotentiary: (n.) a person, especially a diplomat, invested with the full power of independent action on behalf of their government, typically in a foreign country.

- Precentor: (n.) a person who helps facilitate worship. The details vary depending on the religion, denomination, and era in question. The Latin derivation is præcentor, from cantor, meaning “the one who sings before”.

- Sapper: (n.) predecessor to the Bunsen burner, a small lamp that ran on ethanol.a soldier responsible for tasks such as building and repairing roads and bridges, laying and clearing mines, etc.

- Sheeny: (n.) a derogatory term for a Jew.

- Slops: (n. plural) liquid or wet food waste, typically fed to animals.

- Spirit Lamp: (n.) predecessor to the Bunsen burner, a small lamp that ran on ethanol.

- Thraldom: (n.) the state of being in slavery or bondage to another person.

- Variegated: (adj.) exhibiting different colors, especially as irregular patches or streaks.

- Vermiform appendix: (n.) the appendix. The term “vermiform” comes from Latin and means “worm-shaped”.

- Vivisection: (n.) the practice of performing operations on live animals for the purpose of experimentation or scientific research (used only by people who are opposed to such work).

Leave a comment